Last summer, painter Sophia Kayafas, visiting instructor of foundation at Pratt, fostered connection among fellow artists working in Brooklyn as one of the hosts of the documentary series Flowstate/North Brooklyn Artists. Through studio visits and intimate conversations, Kayafas and cohost Ralf Jean-Pierre illuminated the practices of 16 artists in Greenpoint, Williamsburg, and Bushwick—including Pratt alumni Derrick Adams, Lisa Corinne Davis, Coby Kennedy, Fara’h Salehi, and Buket Savci—during a time of uncertainty and transformation. As the series aired on WNET’s ALL ARTS platform this spring, Prattfolio touched base with Kayafas to pay a virtual visit to her studio and learn about her evolving practice.

On the space

When we checked in with Kayafas, she had recently begun inhabiting her studio solo, after a few years of sharing with fellow artists—a situation that reinvigorated her practice. To make the most of this new setup, she arranged the space to quiet internal and external chaos and activate the work.

“I inhabit this space with freedom of thought in mind,” Kayafas says. “I like my work space clean, open, and inviting for a good workflow energy, with enough space to make a mess and forget the world outside.”

Clear zones for different modes of practice help the mind release and focus. “I have [the studio] organized for maximum space on the walls and the most easy access to supplies I need in accordance to my favorite mediums and methods of working,” she says. “They tend to feed and enrich each other. I have a drawing station, a small comp/color-study painting station, a sculpting station, a desk/research writing station, a commission station, and, of course, the other three walls are each large painting stations that revolve images constantly.”

On process

Engaging with different media often helps Kayafas enter the work. “I love starting the studio day with drawing to find flow and freedom of thought and then bringing that mindset to sculpting,” she says, finally transferring “that physicality, familiar visual language of form, and robust attitude to the paintings.”

Kayafas’s practice incorporates repetition and what she calls “sustained patient mystery,” allowing many works to simultaneously resolve over time. Rotating and repeating images, letting them sit over time, and making subtle shifts along the way “until they find a fullness and clarity” is central to the process. “Working on many images and ideas at once relieves me from crippling pressure weighing on the success and conclusion of just one image,” she says. “It allows me to ‘fail’ and experiment without the work crushing me.”

Allowing space for work to happen, free of judgment, is something she encourages in her students as well. “I would love for my students to embrace an approach to failure and experimentation that requires them to be secure with themselves, compassionate toward themselves, and truly curious!” she says. “To let ourselves make and to let it exist, this is a muscle that is always being strengthened in the studio, even when we are alone. Pride can leave us docked on one of two islands—the first being complacency, the second being self-loathing and -deprecation. Both are toxic lies for the creative spirit to house. We must be vigilant and keep moving through the vast beautiful ocean and trust that we will float. Everything good is there.”

Kayafas is currently using these methods to develop a body of work that converses with themes of prayer and spiritual growth in her Orthodox Christian faith. Through what she describes as a world-building approach, Kayafas is engaging with questions like, What does it look like if we could go inside of an icon? How would a symbolic landscape reflect my real spiritual triumphs and struggles? What does prayer feel and look like?

“I have been painting a woman with long flowing hair, moving through this world encountering different things,” she says. “I have many drawings, sculptures, and paintings exploring her presence in this space and her interactions with otherworldly presences, and creatures that live there. Many of my new drawings and sculptures will soon become huge, bold, colorful paintings this summer.”

Three significant objects

Kayafas mixes paints on a glass-topped taboret, an old metal painting table that she notes has received a few coats of spray paint over the years. “This was given to me by a past professor I love dearly,” she says. “Although, the greatest gift he ever gave me was to never define art for me, in any way—no matter how many times I asked him to! This gave me an expansive, inclusive, and ever-evolving approach to art. I think of him when I use this every day. It’s very functional as well.”

“I always come back to the self-portrait to help me anchor myself again when I am feeling lost,” Kayafas says. As part of that process, she uses a custom mirror from her late grandfather’s former business, a glass and mirror company called Olympic Contracting—a “naively kitschy nod,” as the artist puts it, to the family’s Greek ancestry. It was cut especially for Kayafas after his passing, before her family sold the business. “I like looking at my reflection with him in mind. He was a good man.”

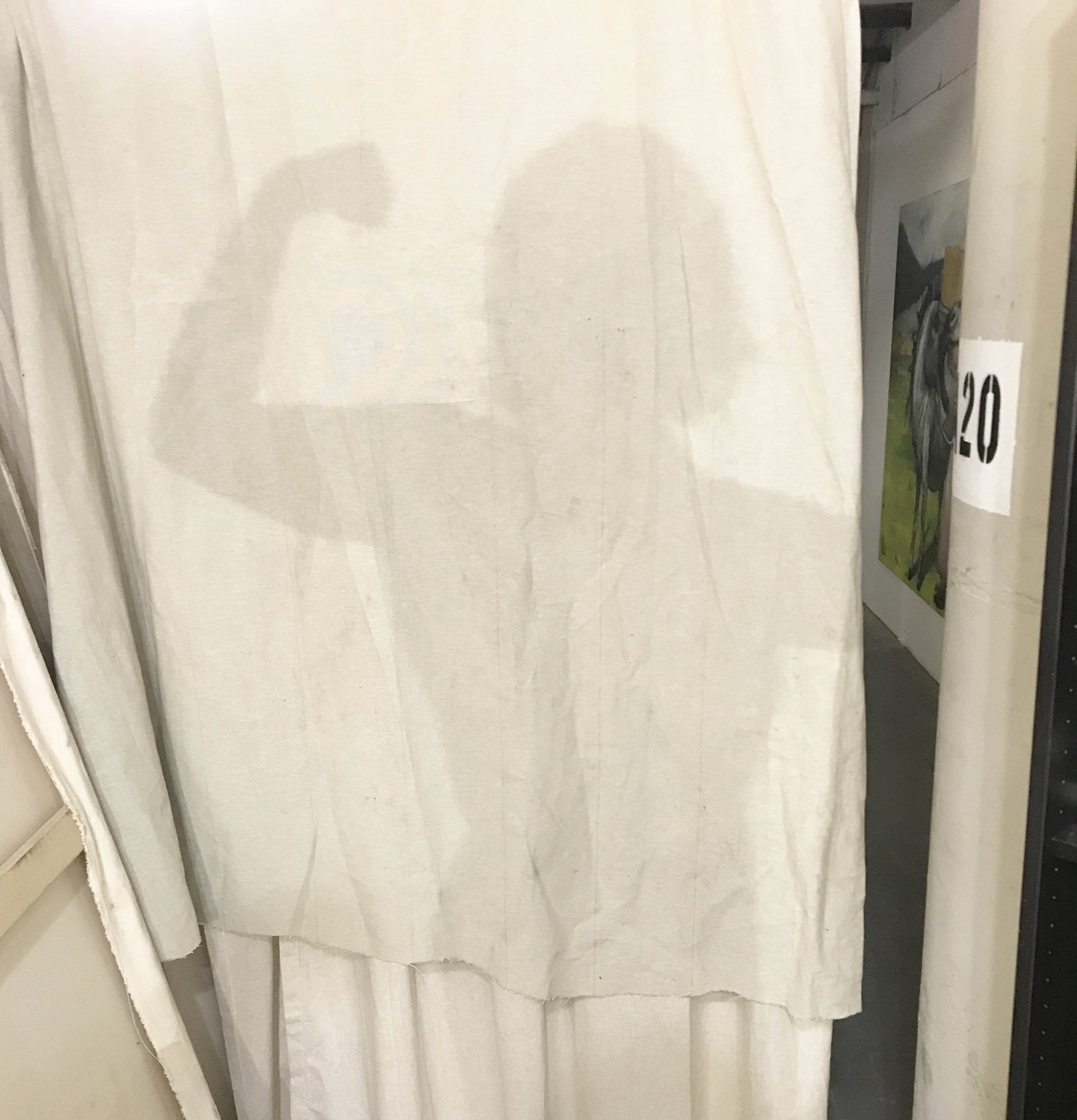

A curtain in the doorway is another essential object whose significance has accrued over time. “Our studios have no doors or walls that go to the ceiling. I recently realized that I like this curtain more and more,” Kayafas laughs. “The privacy that it provides has become surprisingly instrumental in a process of increasing risk and vulnerability.”