From the pages of Prattfolio, this article is part of a series of conversations between faculty and students on the subject of student work. This installment features Duks Koschitz, Associate Professor of Undergraduate Architecture, Director of the Design Lab; Che-Wei Wang, BArch ’03, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Undergraduate Architecture; David Franck, BArch ’18; and Adin Rimland, BArch ’18.

Duks Koschitz and Che-Wei Wang’s architecture studio, Designing Machines that Design, prompted students to dig into the underpinnings of design—such as coding, prototyping, and machining—toward the creation of their own 2-D and 3-D design apparatuses. Ultimately, student teams interpreted their machines’ output as architectural ideas—but much of the studio’s conversation centered on “noise and mistakes and failure, breaking things and fixing stuff,” as Koschitz says, to build students’ technical mastery and confidence to take risks in their work. Adin Rimland and David Franck’s investigation involved a mechanical drawing apparatus; a 3-D-modeling lathe machine that extruded hot glue and wax; and a bridge-based architectural proposal.

DUKS KOSCHITZ: The first step was inspired by an idea that [Daniel] Libeskind had—using a chaotic machine to write about architecture, which he translated into a machine with chaotic behavior that creates a drawing. We expanded on this idea by asking students to interpret their work as architectural speculations.

CHE-WEI WANG: This studio’s big question was what would happen if we wrote our own software, built our own machines—would we come up with a different type of architecture?

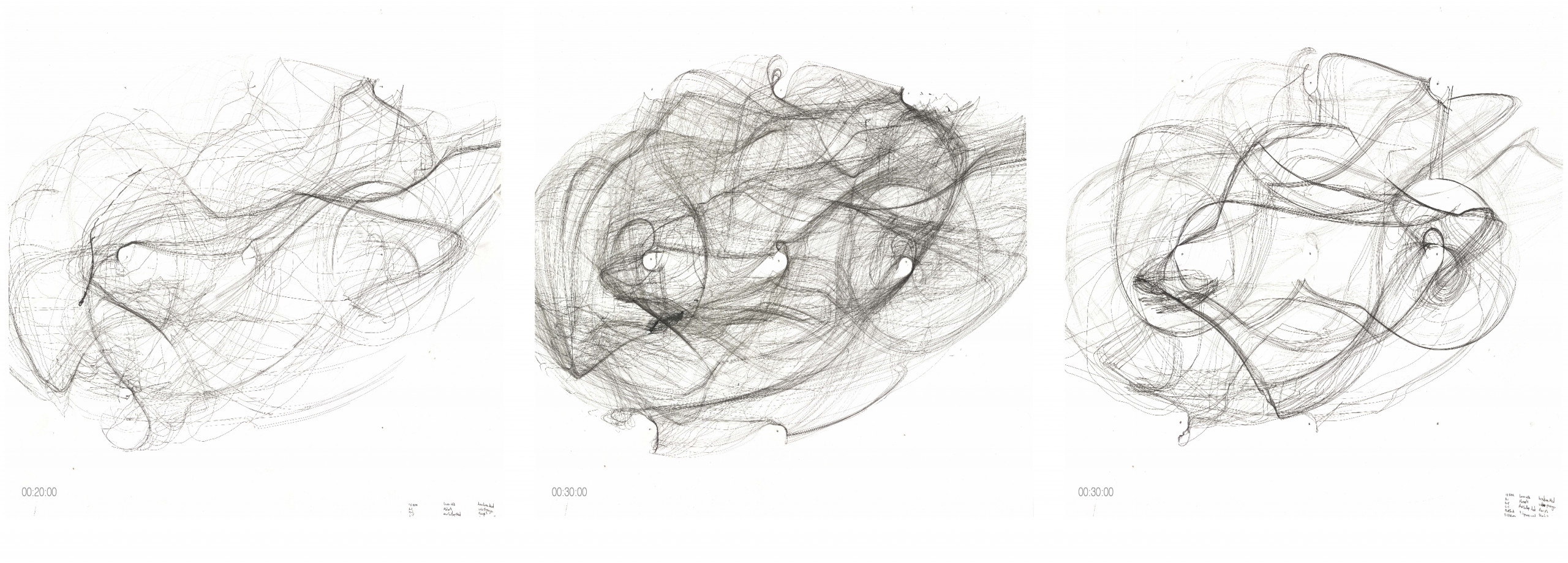

ADIN RIMLAND: We were excited about building this harmonograph [pendulum-powered drawing machine]—you have two different-size wheels, and it creates this shape that embodies two extremes, very clean, mathematically pure.

DAVID FRANCK: Then we went through a process of disturbing that very pure shape, finding interesting things along the way (above).

AR: Introducing elements of chaos into the system—whether adding spring steel to the arm so it would have a kickback or hitting it with a hammer at a steady pace—allowed us to get some kind of, what we felt as ownership, over this machine process.

DK: That’s a nice way of putting it. You’ve got a cyclic system, you start to modify it, and you thereby take ownership of it.

CW: I’m sure you thought about it—to what end are you modifying the machine, how do you evaluate whether the turnout is good or bad?

AR: If we got something novel, that was a success in a way. If we could conceive the final result before doing the experiments, we would consider that a fail—or not a step forward.

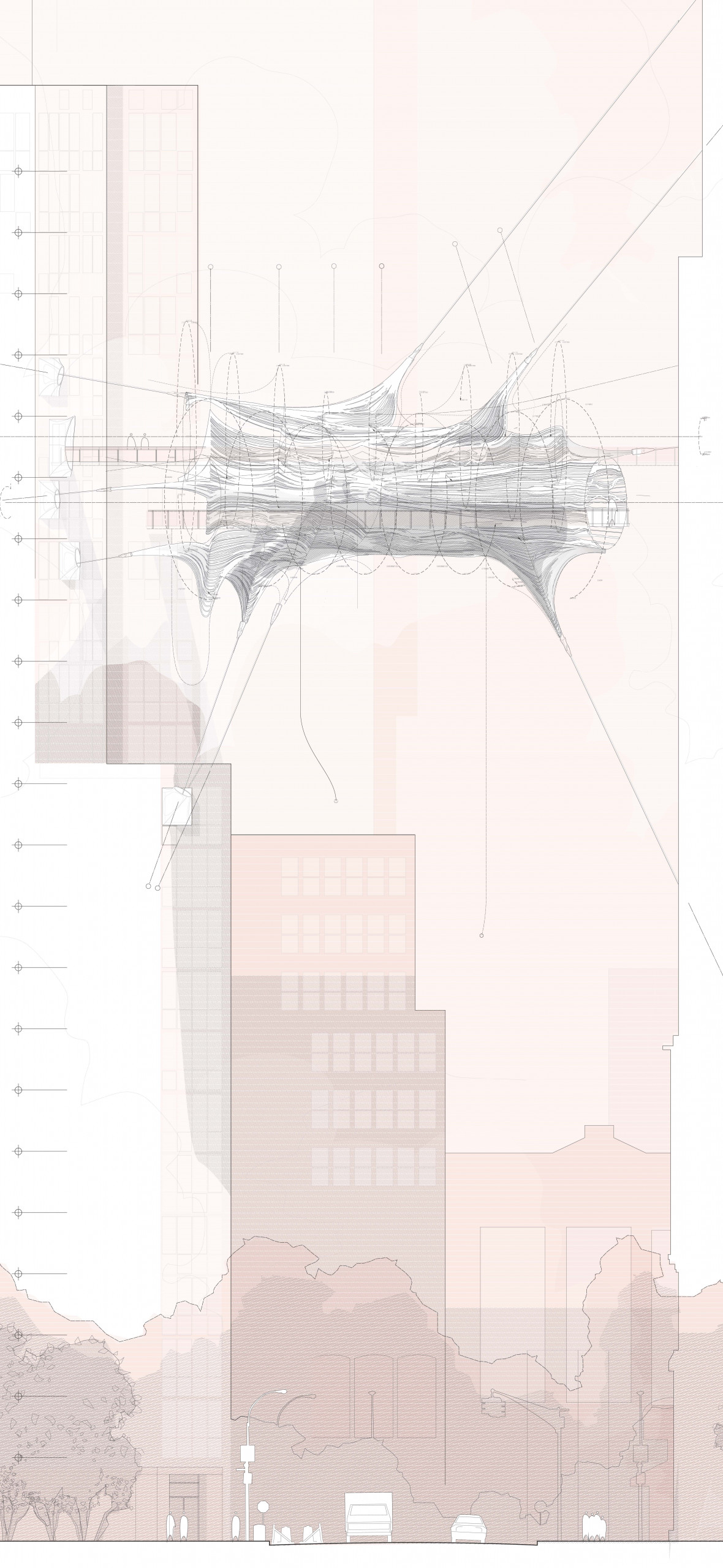

DF: With the final project [3-D drawing machine] we would try to break out of that definite torus, or cylindrical shape.

DK: So normally you would just spin around one axis. You used two, and put [the formwork of the model] into the machine in one orientation and then a second time in another orientation. That’s how the geometry of this occurred. How did you make the decision to open up the ends?

DF: That was partially to have the potential of hooking into a building, to create a sort of parasitic architecture.

AR: So we developed those jig endpieces, those laser-cut fingers—

DF: To hold it open, the metal pieces playing the role of tension cables.

DK: It’s nice to hear both of you describe which piece is doing what. We’re reading into not the drawing but the model—it shows you that making a three-dimensional sketch and then looking for architectural potential does work. You can get physical data that a drawing can’t give you.

DF: Materials do interesting things, and being able to read them as architectural elements might force you to rethink the way a wall works or a floor works.

AR: For instance, in our final test, we had these catenary curves that started happening—these lacy curves—it was like the material acting at its most pure, and the form acting to service the material.

DK: How would you say all this was productive for a thesis?

AR: There were a lot of techniques, a lot of troubleshooting.

CW: It’s interesting that in architecture school, there’s some hesitation to just absorb technical knowledge, but you enjoyed it. There’s a huge value to it in that it gives you more agency, more confidence to take on things that you really want to.

DK: Would you say you’re less afraid of trying something?

DF: Yes, I mean—to learn anything, you have to take risks. And if you do it properly, document properly, you will end up learning.