Every neighborhood is made up of layers of planning design, where decisions about what to preserve, prioritize, and build have shaped the architecture, greenspaces, and streets. Weeksville in Brooklyn has particularly deep layers of that history as the site of one of the first free Black settlements in the country founded in 1838.

Students in Co-Designing Brooklyn’s Hidden Heritage: The Weeksville Experience working with drone pilot Tishawn Fahie

Every neighborhood is made up of layers of planning design, where decisions about what to preserve, prioritize, and build have shaped the architecture, greenspaces, and streets. Weeksville in Brooklyn has particularly deep layers of that history as the site of one of the first free Black settlements in the country founded in 1838. Its footprint was later lost beneath the development of Crown Heights. Then in 1968, its surviving 19th-century structures were rediscovered due to their orientation to an old trade road rather than the modern streets. In the fall semester, undergraduate and graduate students in the Pratt School of Architecture collaborated with Medgar Evers Preparatory College High School (MEPCHS) students in Crown Heights to examine the past and present of Brooklyn so that the local students can be empowered to have a voice in their neighborhood’s future.

Co-Designing Brooklyn’s Hidden Heritage: The Weeksville Experience was developed by Carisima Koenig, visiting assistant professor in the Graduate Architecture and Urban Design (GAUD) program, and Scott Ruff, adjunct associate professor of undergraduate architecture, with funding by the IDC Foundation.

“Weeksville was chosen because it is an inspirational African American narrative,” Ruff said. “To know that our ancestors occupied, worked, and settled in this land before it was Brooklyn can develop a sense of belonging and legacy. It is generally believed that African Americans migrated from the South to the North seeking industrial jobs in the early 20th century. Although that is true, it is not the whole story; the existence of Weeksville offers proof that large numbers of organized freed African Americans were living in the North and they dared to make a life where they not only survived but with the hopes and aspirations to thrive and prosper.”

They used the Weeksville Heritage Center established at the site of the historic Black neighborhood as an example of activism and advocacy through design and engaged the 18 participating MEPCHS students in the now invisible larger presence of Weeksville which encompasses parts of today’s Crown Heights, Brownsville, and Bedford Stuyvesant.

“Design agency and understanding how a city works were an important part of the curriculum,” Koenig said. “Typically, we operate on the ground level as we negotiate the city and this was true for the high school students. With our School of Architecture student mentors, we were able to show a different view through architectural technologies of seeing—drones, maps, and plans expressing the view city planners and architects have access to. There is something empowering in toggling between the ground-level experience of the city and the organizational techniques a city employs and how spaces that are hidden can be uncovered.”

Students in Co-Designing Brooklyn’s Hidden Heritage: The Weeksville Experience working with drone pilot Tishawn Fahie

In addition to the Pratt architecture students gaining experience in teaching and collaboration, the high school students got time in the studio culture of higher education and the profession of architecture. These insights allowed them to see themselves in creative careers and be inspired to have agency in improving neighborhood spaces in their communities.

“We worked with the students to help them find the things they would like to change in their neighborhoods and then aided them in brainstorming how that would look architecturally,” said CJ Spring, BArch ’22. “I feel like we hear a lot about high-profile architecture projects, but not so much about smaller, intimate projects that aim to fix specific social issues. By working with the students, it helped me understand that we need to focus on encouraging people from every background and walk of life to take up architecture because they are the ones who know what their community needs most.”

With the two faculty leads, the Pratt students developed and taught the curriculum for the MEPCHS students. As Co-Designing Brooklyn’s Hidden Heritage was envisioned as an interactive studio to introduce the high school students to the academic and professional fields of architecture, it had to be adapted to the safety guidelines of the pandemic.

“We had some key structural issues as we had to take a curricular experience that is normally consolidated in time and meeting space and distribute it in smaller packets and across multiple platforms,” Koenig said. “The Pratt student mentors were the glue for the high school students—exploring new platforms for teaching and learning—building upon their own experiences.” This included their adaptation in the shift to online and hybrid learning last year.

“Through online learning, we’ve been able to make the most of the experience by thinking about what they may or may not have at their disposal like drafting tools and software,” said Luz Wallace, MArch ’21.

A series of workshops involved at-home learning kits to tackle various aspects of design, activism, and community development, from looking at their surroundings through its architectural elements to understanding how zoning has impacted New York City. “Community-based projects such as this need organization and collaboration from multiple stakeholders,” said Maria Cecilia Concepcion, MArch ’21. “One of the best courses of action is to meet them where they are.”

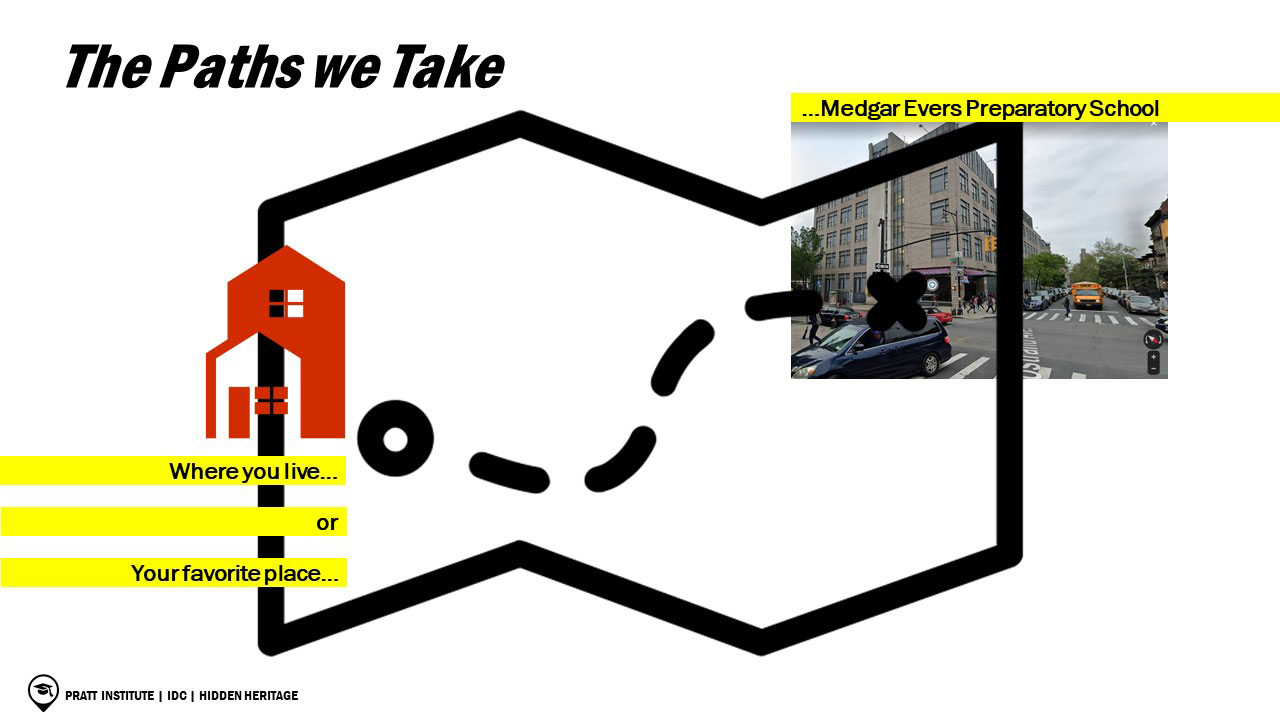

By mapping their preferred paths to high school and identifying areas with potential for positive improvement in their neighborhoods, the MEPCHS students proposed projects that could respond to their community’s needs while reflecting on its rich history. One was on public health and how healthy neighborhoods impact their community and citizens while another was on community and gathering spaces for high-school-aged students, offering them a place where they could express themselves, socialize, and connect. They spent time researching Weeksville on the ground and in the air, with the Pratt architecture students partnering with FAA drone pilot Tishawn Fahie to capture aerial footage. Employing both 2D and 3D modeling, the high school and Pratt students connected on using planning, design, and architecture to advance their ideas.

“While working with the high school students, I was constantly reminded that architecture starts local,” said Onyi Egbochue, BArch ’21. “Once the students were able to deploy their design skills, it was amazing to watch them envision what a safe and healthy community is for them and what architecture looks like in their eyes.”

Important to this design analysis was investigating the area’s past to consider how to celebrate its history in the present and future. Weeksville was founded by James Weeks just a decade after slavery ended in New York and became a self-sufficient Black community that included businesses, churches, schools, a newspaper, and a cemetery. By researching and exploring this heritage, the students learned how to be investigators of the neighborhood’s built environment.

“It challenged me to be more critical and observant about the spaces around me,” said Jade Ayodeji, BArch ’22. “I’ve always been interested in doing community engagement work so getting that hands-on experience has been amazing. I have really enjoyed this opportunity to pass on what I’ve learned in architecture school to high school students with a budding interest in architecture.”

Pratt has a long connection to Weeksville, with a class offered by the Central Brooklyn Neighborhood College, spearheaded by the Pratt Center for Community Development and the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council, leading to the identification of the Hunterfly Road Houses in 1968. Weeksville also figures in the recently released In Search of African American Space: Redressing Racism anthology of essays edited by Ruff and Professor of Humanities and Media Studies Jeffrey Hogrefe with Ashley Simone, visiting assistant professor of undergraduate architecture, and Carrie Eastman. The next steps for Co-Designing Brooklyn’s Hidden Heritage: The Weeksville Experience will include an exhibition planned for the fall that will showcase the work of the MEPCHS and Pratt students, featuring a film documenting the program’s process and outcomes.